The Moken are a group of Austronesian people of the Mergui Archipelago, some 800 islands claimed by both Myanmar and Thailand, their population comprising two to three thousand people who live and make their living in and on the ocean, a way of life that seems totally primitive to our modern view, but that contains certain values and behaviors that might be exemplary for us all.

I am not going to propose here that we all return to what many would consider a backward, primitive life, deprived of all the modern comforts of life, the benefits of consumerism, the security of what we call civilization. But there is a movement among us for a much simpler life: some opting out of the consumer matrix, some defining comfort and safety in different value terms that are not just romantic or idealistic fantasy, but are rather another form of modern engagement with land and sea in the context of sustainability and community.

Where I live I am surrounded by young farmers and fishers engaged in organic agriculture or the harvest of marine species, gathering and hunting if you will, in a simpler world that is not primitive at all. The Moken have accumulated a vast knowledge of the sea, and while they harvest with spears and nets, dry and prepare products on the decks of their floating homes, bartering and selling at local markets, these habits are not so much removed from what occurs in my local farmers’ market of a Saturday throughout the year: farmed meats and dairy, fish and shellfish, winter vegetables, prepared foods, baked goods, sea salt distilled from out local waters, and other unique products for which I gladly exchange for value.

Of course the Moken are under extreme pressure from government policies of assimilation, language suppression, relocation, and subversion of cultural traditions. Why is it that governments fear the other? There are such consistent attempts to suppress freedom to live apart, with art and tradition that is nothing more dangerous than a continuity of personal expression and collective belief. We see it everywhere that minorities dwell, especially when these communities rise up to protect what is to them both worldly and sacred value. Look at religious conflict in Arabia, tribal conflict in Africa and China, racial and ethnic conflict in Europe and the United States: you’ll discover the same, underlying opposition to diversity and identity, be it by dictators, monolithic governments, corporate dominance, religious uniformity, and all the other structures that work — sometimes together — to oppress, suppress, even eradicate these last vestiges of cultures.

If we are paying attention, these cultures may provide us wisdom by which to transcend ourselves, our consumption, our need to reduce the world to one simplistic structure over which centralized authority presides.

If you look at the reasons for government attempts to relocate and domesticate the Moken, you need look only to offshore oil discoveries in the surrounding waters by Unocal, Petronas, and other international energy companies to understand the political pressure to relocate the Moken to the alien mainland, out of sight, out of mind, out of the way of the environmental impact of drilling and mining and all the other morally bankrupt financial enterprise of the past, proven so destructive on land and now to be so comparably destructive at sea. If the new definition of civilization is to repeat the corrosive and corrupting behaviors of the past, this small event in a place far away is but another example of that decline.

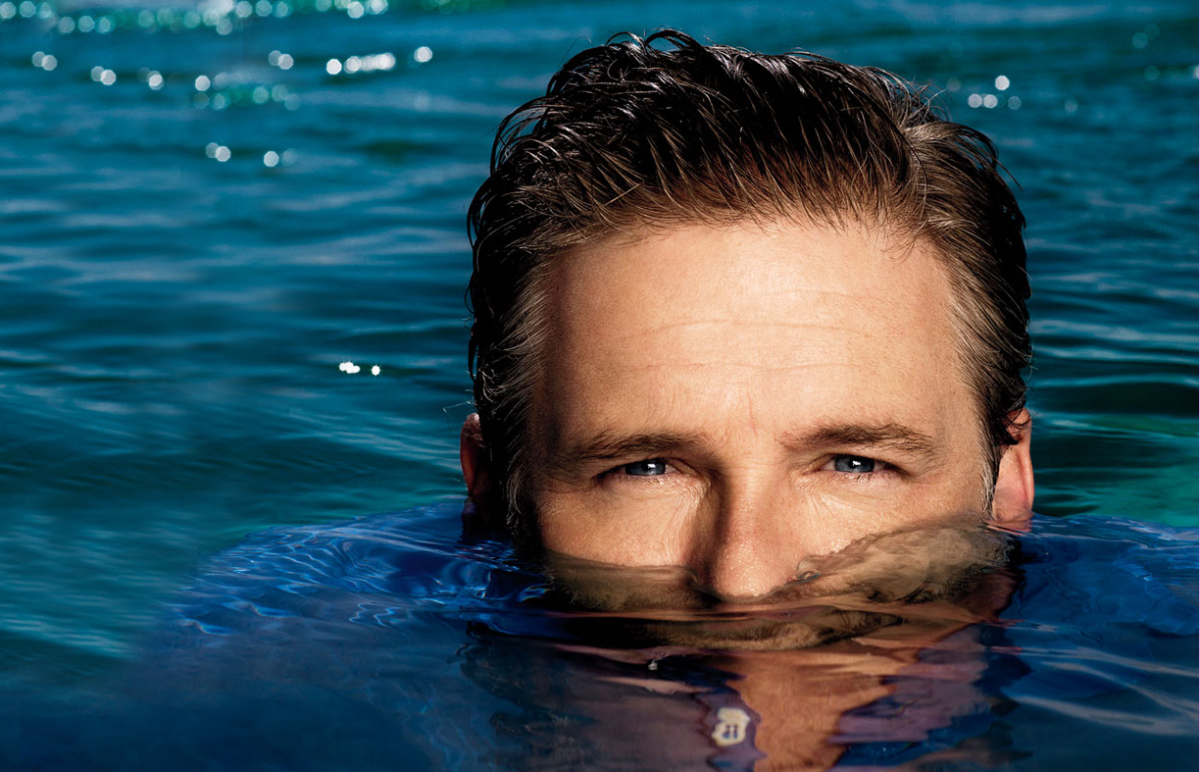

Various anthropologists and scientists have studied the Moken as some kind of vestigial leftover from the past. Interestingly, they discovered that Moken children have superior underwater vision to European children, an hypothesis theorized and confirmed by a comparative study of physiology and visual acuity by a Swedish scientist. The explanation posited was constriction of pupils and accommodation of visual focus to the specific conditions. Moken children see differently than we do, a behavior conditioned by the circumstances of survival — gathering mollusks, marine plants, and fish for protein. The European children were further debilitated by sustained temporary red eye that left them blind to the harvest.

Some look at the ocean and see oil and gas; these are the red-eyed ones. Others look at the ocean and see community and sustainability; these are the clear-eyed ones — sea people, shaped by the past, reacting to the present, and looking at what must soon come to be. We are among them; we are all Citizens of the Ocean; we are all people of the water.